Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'tamil tiger women'.

-

Source: https://academic.oup.com/book/5982/chapter/149349981 Abstract This chapter discusses the motives and legitimation of female cadres of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) joining the fight against the Sri Lankan government. Tamil young women were, among others, motivated by grievances against the treatment of the Tamil minority by the government, their experience of sexual and gender-based violence by Sinhalese soldiers and Indian peacekeepers, and a wish to avenge the death of relatives. They also wanted to escape a suppressive and conservative Tamil culture that forced them into arranged marriages. The heroism and sacrificial martyrdom cultivated by the LTTE legitimized these women’s combat role among the Tamils in Northern and North-eastern Sri Lanka who admired their courage. Different societal and theoretical discourses exist concerning the supposedly victimizing, liberating, or empowering effects of female participation in armed struggle, but the situation in reality appears to be ambivalent, including both victimhood and emancipation. ----------------------------------------------- 1. Introduction This chapter discusses the experiences of the female cadres of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) which fought a twenty-six-year separatist war against the government of Sri Lanka. The participation of women and girls in this armed struggle could in and of itself be considered as quite remarkable, as the behaviour and practices required from a female LTTE fighter were completely at odds with the prevailing gender norms and practices of traditional Tamil society and culture. Therefore, apart from motives that can be found more widely to join militant movements (ideology, nationalism), what motivated Tamil girls and women to join the movement? This chapter shows that Tamil young women were particularly motivated by feelings of revenge against the Sri Lankan state and army, an urge to escape a suppressive, conservative, and caste-minded Tamil culture that restricted their movement and favoured arranged marriages, as well as to flee domestic violence and abuse. The chapter discusses the role of LTTE women in combat during the twenty-six-year-long war and how this role was legitimized both from their own perspective and in the eyes of the public in Northern and North-eastern Sri Lanka. The chapter is based on field work in Sri Lanka, earlier work by the author on the nexus gender-conflict, and secondary sources.1 The fieldwork in Sri Lanka was done in the framework of a research project funded by the Gerda Henkel Stiftung that was carried out in 2014, 2015, and 2016 by me and co-researcher Niels Terpstra. This project focused on how the LTTE governed the spaces under their control and how their rule gained legitimacy either through the use of conscious legitimation strategies or more generally through behaviour and practices that legitimized them in the eyes of the population.2 In 2014–2015 we focused on LTTE governance and conducted seventy-six semi-structured interviews of over two hours with community members in twenty-one different locations in the Eastern and Northern provinces. A total of twenty key informants, such as civil society and community leaders, NGO workers, religious leaders, doctors, ex-LTTE cadres and supporters, and local government officials were also interviewed. In 2016, we conducted interviews with another sixty-two respondents about popular support for and legitimation of the LTTE in the Trincomalee district and throughout the Northern province. We conducted the interviews with key informants, and used a team of eight field researchers for the semi-structured interviews, in view of language requirements. This team was working for a local research NGO and wishes to remain anonymous due to security and safety reasons. They were trained by us in several workshops, while we also held debriefing sessions. Notes were made of all interviews and the resulting Tamil reports were translated in English by a professional translator, after which they were coded and analysed by us with the help of NVIVO software. The translations, and working with different researchers, may have led to some loss of content and perhaps a less systematic probing then we ourselves would have done. In order to redress this, we have triangulated our different data sets where possible and also extensively used secondary material. This chapter uses selected quotes from interviews of this larger study as they are pertinent to the topic of this chapter. These interviews are indicated by a code in the respective footnote. Section 2 gives a brief general description of women’s roles in war, and Section 3 provides a short overview of the Sri Lankan conflict. Section 4 describes the rise of Tamil militancy and the LTTE. Section 5 concentrates on the female fighters of the LTTE, and is followed by the conclusions in Section 6. 2. The Role of Women in War: Women as Fighters War, and its corresponding battles and violence, have long been considered as male domains of activity. However, it has been increasingly recognized that women not only are affected by war (victims, refugees, internally displaced, widows, and sole breadwinners, etc.), but are also actively involved in it. Elsewhere we have extensively discussed the variegated roles women play in conflict (Bouta, Frerks, & Bannon 2005). Frequently, discussions only focus on women either as war victims or as peace activists, following prevailing gendered, stereotypical notions on the nature of womanhood in society, for example, that women are ‘naturally’ more peaceful than men, i.e. they are mothers who do not like to see their children killed in war.3 Such an essentialist approach is highly problematic, although in many societies women are expected to behave according to such stereotypes. This chapter transcends these essentialist notions of women’s victimhood or peacemaker’s role, and focuses on LTTE female combatants as ‘perpetrators of violence’. Traditional war-time female support roles, e.g. cooks, spies, soldiers’ wives, have changed to include perpetrators—women who commit violent acts as members of armed militant, liberation, insurgent, or ‘terrorist’ movements on their own. Women have been part of regular and irregular armies throughout the world and throughout the ages, and in fact often comprised a significant part of those armies. Estimates include El Salvador’s Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMNL): 25 per cent women; Sandinista National Liberation Front in Nicaragua: 30 per cent; Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF): 34 per cent; Liberia: 38 per cent, East Timor underground resistance: more than half; and the Lord Resistance Army (LRA): about one-quarter girls.4 Based on worldwide data-gathering covering the period 1990–2003, McKay and Mazurana found that women/girls are part of fighting forces in fifty-five countries, of which thirty-eight saw women involved in actual conflict (McKay & Mazurana 2004, 21). Increasing numbers of studies are being made into the reasons women join these struggles. For example, Brett and Specht’s early (2004) publication titled Young Soldiers: Why They Choose to Fight, highlights that war itself can induce young people into violence because of sheer need (poverty, loss of family, closing of schools, protection) or the chances it provides in terms of employment. Family ties, friendship, and peer pressure also play a role in recruitment as well as ideological and political persuasions. Section 3 briefly introduces the Sri Lankan conflict, Section 4 the LTTE militancy, and then further sections focus on the female LTTE cadres and investigate reasons they joined this movement. 3. The Sri Lankan Conflict The Sri Lankan conflict has long historical roots, but the overt, separatist war between the LTTE and the government of Sri Lanka occurred between 1983 and 2009, when the LTTE suffered a military defeat at the hands of the Sri Lankan Armed Forces. Earlier attempts to resolve the conflict, e.g. the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), direct and indirect (international) negotiations, facilitation by the government of Norway, failed. The conflict has been described and explained in many ways. It concerns a complex political crisis that defies a monocausal explanation. Political grievances, competing ethno-nationalisms, ethnicized politics, failed nation-building, religious intolerance, and bad governance are among the major factors seen as contributing to the genesis and escalation of the conflict. The war has caused over 80,000 casualties5 (of which 27,000 were soldiers from the Sri Lankan Armed Forces), while one million people fled the country, and some 800,000 people were internally displaced, often multiple times. The conflict undermined the economic stability and development of the conflict areas and of the country as a whole. The war further affected Sri Lanka’s erstwhile good human rights record and led to a militarization of society (Mel 2007). It also led to increased ethnic and social divisions and mutual distrust between the different identity groups as well as economic disparities between the war zones and the rest of the country. In the scope of this chapter I suffice with this brief summary, as the conflict has been documented extensively by a variety of Sri Lankan and international scholars and experts.6 4. The Rise of Tamil Militancy and the LTTE Although Tamil nationalism has a longer history, it became prominent after Sri Lanka’s independence7 in 1948. Immediately after independence the then-Sri Lankan government, dominated by the majority Sinhalese, disenfranchised one million Indian Tamils who had been brought from South India as plantation labourers by the British in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This disenfranchisement created anxiety among other minority groups as well, such as the Muslims, Burghers, and the Ceylon or Jaffna Tamils, who had lived in the Island for over 2,000 years. In 1956, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party came to power pushing a Sinhalese ethno-nationalist agenda. The government declared Sinhalese the only official national language (‘Sinhala-only’) at the detriment of Tamil and English, effectively excluding Tamils from government jobs (de Silva 2007, 213–36). In response, the (Tamil) Federal Party (FP) demanded a federal state comprising a separate Tamil-speaking Northern and Eastern part and a Southern Sinhalese part, and wanted both Sinhala and Tamil to be recognized as official languages. It further demanded a stop to state-aided colonization by Sinhalese farmers in Tamil areas. Sinhalese mobs attacked non-violent demonstrations and protests by the FP against these government policies, and anti-Tamil violence spread across the country in which Tamil shops were attacked and looted. The police, however, did not interfere (Swamy 2002, 10). Swamy and Wickramasinghe assert that an estimated 150 Tamils died in the riots, including women and children (Swamy 2002, 11; Wickramasinghe 2006, 272). In May 1958, there were again Sinhalese–Tamil riots that left 300 (mainly Tamils) dead and over 1,000 injured. Wickramasinghe states that ‘politically motivated Buddhist monks and rowdy elements organized anti-Tamil rioting in all parts of the Island’ (2006, 272). Clarance (2007, 37) observes that ‘From this critical moment, the Tamils realized that they could no longer rely on the state to protect them.’ In the 1960s and 1970s controversial colonization schemes in Tamil areas were implemented, while the so-called educational standardization hampered Tamil students’ access to university. Finally, the 1972 constitution awarded special protection to Buddhism (an almost exclusive Sinhalese practice), while the earlier clause protecting ethnic and religious minorities was removed. There were also episodes of violence against Tamils in several parts of the country, often with the connivance or complicity of the state and the police, and impunity of the offenders. These developments together created a deep feeling of concern and alienation among the Tamil population in Sri Lanka. In the meantime, the major Tamil political party, the FP, proved unable to achieve any results in a series of negotiations with the government between 1956 and the early 1970s. In 1972 the various Tamil parties joined into the Tamil United Front, to be renamed into the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). At its first convention in Vaddukoddai in 1974, the TULF resolved that it wanted to establish a free sovereign state of Tamil Eelam based on the right of self-determination in order to safeguard the very existence of the Tamil nation. However, Tamil youth, who saw no future for themselves and were disgruntled and disappointed by the ineffective elderly Tamil political leaders, took matters in their own hands. Tamil parliamentarian nationalism and the option of non-violent action had lost their appeal, as they were perceived as having failed to deliver any meaningful results to the increasingly frustrated younger Tamil constituency. From the late 1960s and early 1970s onwards, restless young Tamils started to organize themselves in a variety of radical political groups. As early as 1967, students from St. Patrick College in Jaffna had set up the Eelam Thamil Elangar Eyakam (Eelam Tamil Youth Movement, ETEE) in protest against the government’s educational policies and overall oppression. In 1969, the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization (TELO) was created, with the young Vellupilai Prabhakaran (the later LTTE leader) as one of its members. On 27 July 1975, the Tamil New Tigers (TNT), under the leadership of Prabhakaran, killed Alfred Duriappah, the SLFP’s Tamil mayor of Jaffna who was seen by the militants as a government collaborator. On 5 May 1976, Prabakharan founded the LTTE. A group of Tamils in London formed the Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students (EROS) from which the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPLRF) later separated. In those early days of Tamil militancy, there were more than thirty groups, differentiated by caste (karayar, vellala),8 region (Jaffna, Mannar, Batticaloa, Amparai), ideological position (nationalist, revolutionary, Marxist, etc.), and allegiance to individual personalities. Several militant factions had produced or acquired arms, with some receiving guerrilla training with the help of India, but also, in the case of EROS, support and training from the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) in Lebanon. Over time, these groups would not only attack the common enemy in the form of the Sinhalese state, but also target each other in a search for exclusive leadership and ideological hegemony (Wilson 2000, 126–7). In the second half of the 1970s, the situation in the North of Sri Lanka grew increasingly violent. Tamil protests, attacks, bomb explosions, and assassination attempts led to widespread arrests, imprisonment of suspects without charge or conviction, torture, and ‘a reign of police terror in the North’ by the government (Bandarage 2009, 69). Since 1976, Prabhakaran further developed the LTTE, trained new recruits, and gave it a logo, a central committee, and a constitution. The LTTE started to engage on a significant scale in armed skirmishes with the Sri Lankan army from the late 1970s onwards. It committed a series of (bank) robberies and murders of policemen, for which it claimed responsibility in letters to the press, and blew up an aircraft at the Ratmalana airport close to Colombo. They also initiated a propaganda campaign outlining the Tamil struggle (Swamy 2002, 64–5). Anton Balasingham, a journalist and academic, joined the LTTE and gave ideological classes to LTTE members, further developing its political and ideological stance. The conflict between the Government of Sri Lanka and the LTTE surfaced internationally as an open and violent conflict in July 1983, when thirteen Sinhalese soldiers were ambushed by the LTTE in Tirunelveli in North Sri Lanka. Riots broke out in Colombo killing hundreds of Tamils (although estimates go up to 3,000 casualties) and damaging the homes and livelihoods of probably 30,000 more. An estimated 100,000 Tamils were displaced in Colombo and 175,000 fled abroad (Clarance 2007, 44–5). The violence in Colombo was planned with the participation of politicians and government staff, and with the use of government vehicles. The rioters also had voters’ lists and the addresses of Tamil homeowners and shop owners (Tambiah 1996, 94–7). Observers have also noted that the government did not act to stop the violence and only declared a curfew when the worst was over. The July riots in 1983 were in many ways a watershed, even seen by many as the starting point of the war, but this is debatable. Wickramasinghe (2006, 287) describes the repercussions of ‘Black July’: On top of that, the various rebel groups also got support from India. The Indian external intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), started training and arming the different rebel groups on a large scale; in total, an estimated 1,200 young Tamils received training in Dehra Dun, close to Delhi, between 1983 and 1987 (Swamy 2002, 102, 110). Those who finished their training in turn trained thousands of new recruits in dozens of camps set up in Tamil Nadu, helped by retired Indian army officers. Swamy states that the numbers trained by 1985 would have equalled or surpassed the strength of the Sri Lankan army (2002, 112). Gunaratne mentions an estimated 20,000 persons that received training and weapons in India (Bandarage 2009, 114). Thiranagama quotes Sivaram’s figure of about 44,800 militarily deployable youth in the years 1984–1985, at that moment of which less than 10 per cent belonged to the LTTE (2011, 187–9). Black July and its aftermath started a full-blown war that was to last over twenty-five years. The fight by the rebel groups between 1983 and 1987 became known as Eelam War I. Three other ‘Eelam Wars’ were to follow. The LTTE grew into a capable and ruthless armed movement that forcefully gained dominance over the other Tamil militant groups to the point where it claimed to be ‘the sole representative of the Tamil-speaking population’. In order to reach that position, it decimated competing groups. Hundreds of TELO and EPRLF cadres were killed from 1986 onwards (Wickramasinghe 2006, 289). The LTTE also became notorious for its forced recruitment of child soldiers, for being one of the first movements to use suicide commandos, and the introduction of the cyanide capsule that cadres had to swallow when they fell into enemy hands. It also started to recruit women for its fighting force and deployed them in combat from 1985 onwards (Manoharan 2003).9 The LTTE also controlled its own territory, first in the Jaffna peninsula from 1990–1995, and from 1995 onwards a self-administered area in Northern Sri Lanka, called the ‘Vanni’. The LTTE set up and ran essential departments such as security, law, police, and development planning themselves, and allowed other government services to continue under their supervision. One respondent told us that the ‘government servants functioned under the instructions of the LTTE. The government appointed and paid them but their duties were performed under the complete control of the LTTE’.10 From this territory the LTTE could not only launch their forces into combat against the Sri Lankan armed forces, but also recruit and train their cadres, and gain popular support for their struggle. A respondent from Mankulam stated that ‘During [the war] the Vanni was under the control of the LTTE. … They made it compulsory that one member of each family should join the LTTE movement’.11 In addition they had varying degrees of influence in other parts of the north and east from where they also recruited cadres either voluntarily or by force and demanded financial contributions or taxes for the ‘good cause’ (Terpstra & Frerks 2017). A housewife from Kilinochchi divulged that ‘Taxes were collected from the shops, fields, and houses. Particularly, [the LTTE] collected tax from the moneyed people and used it for their needs and they helped the needy also from that money. At the time of the harvest cadres of the LTTE would be present. It was compulsory to pay one-third of the income to the LTTE’.12 Another respondent added in this connection: ‘People did not consider taxes collected from them as a burden. They paid the taxes wholeheartedly, and they considered them as taxes to live in the sacred land of the Tamils’.13 Another respondent admitted, however, that ‘they faced hardship’ due to the taxes and that these ‘influenced their cost of living’,14 while a female farmer asserted that the ‘Tax was a burden, but without taxation no organization can survive’.15 5. Female LTTE Fighters Women appeared in the LTTE’s organization in 1983 as the Viluthalai Puligal Magalir Munnani (Women’s Front of Liberation Tigers) and later as Suthantira Paravailgal (Birds of Freedom) (Manoharan 2003). Manoharan states that this was not only an ideological choice to promote social and national emancipation, but was also induced by the fact that, despite a serious shortage of manpower due to casualties and a refugee exodus, the fighting against the Sri Lankan state and the IPKF had to be sustained. According to Manoharan (2003), females accounted for up to one-third of the total LTTE combatants from the mid-1980s onwards, although numbers may have varied over time. Samarasinghe (1996, 214) agrees that the LTTE might well have recruited women due to a shortage of male recruits due to refuge and casualty losses, but that the liberation struggle was simultaneously projected by the LTTE and its leader Prabhakaran both as a medium and a strategy for emancipation. Apart from its struggle for ‘national liberation’, the LTTE purported to aim at a ‘social revolution’ by means of a socialist transformation. Additionally, the LTTE stated in its political programme that: Several independent reports have confirmed that the LTTE changed the traditional Thesawalamai law, proscribed the dowry system, punished rape, and was strict on domestic violence, thus clearly attempting to change gender patterns of traditional Tamil society. Hellman-Rayanagam (2004, 110) notes that ‘The LTTE has pursued both policies (emancipation of women and the interdiction of taking and giving dowry) with great vigour’, and this was confirmed in our interviews. One female respondent noted that ‘Criminals were given severe punishments. People were scared. Child abuse was considered a serious offense … and wife beaters were beaten’.16 5.1 Reasons to join the LTTE McKay and Mazurana (2004, 22) identified the following general mechanisms through which girls enter armed forces and militant groups worldwide: recruitment, joining voluntarily, abduction or compulsory service, being taken as an orphan, born in the force, or being a ‘tax’ payment or war booty. Many women joined in response to local or state violence or to avenge perpetrators of violence. Others joined due to abuse at home. A number joined because their parents, siblings, or spouses already belonged to the forces or armed groups. One female respondent said about the LTTE: ‘They are one within us. They are our brothers and sisters. They are one from our family’.17 Women’s motives for becoming a fighter also include a feeling of solidarity with the goals of the war or movement, and patriotism. In the north of Sri Lanka, for example, the goal of a Tamil homeland was widely shared. One female respondent declared that ‘People expressed their absolute support to this idea. They approved of it’.18 An officer working in the private sector stated that the LTTE ‘fought to protect our country from the Sinhalese. Because of this our people gave them complete co-operation and supported the militants’.19 In the case of the female LTTE fighters nearly all the above-mentioned mechanisms to join applied, apart from war booty. The practice of rebel groups capturing enemy women to work for them or for use as sex slaves was not reported with the LTTE. On the contrary, the LTTE was known to be very strict with regard to sexual abuse, and one respondent testified that ‘Those involved in sex crimes received rigorous punishments’.20 The LTTE suicide bomber Dhanu who blew up Rajiv Ghandi probably acted out of revenge: her home was reportedly looted by soldiers of the IPKF, she was gang-raped, and her four brothers killed (Pape 2005, 226). Hellman-Rajanayagam supports this idea, saying that ‘ … in many cases, women themselves seem to perceive membership in the militant group as a form of liberation, primarily because it is said to be a protection from rape by the ubiquitous rampaging Sinhalese soldiers’ (Hellman-Rajanayagam 2004, 1110). A female teacher we interviewed confirmed that the ‘Sri Lankan Army threatened people and arrested young men and women forcibly. They caught them and took them away. They abused the young women and subjected them to rape’.21 Even in retrospect a respondent working in the private sector highlights the safety under the LTTE: ‘They protected people from theft, murder, and robbery. When the Liberation Tigers were there, where did you find rape? But now rape has increased from place to place. We have to ask where the people’s protection is. The reason for all this is that people have become bold in the absence of the Liberation Tigers’.22 Alison interviewed fourteen female LTTE combatants to investigate the reasons why they joined the LTTE. Nearly all referred to nationalist ideas of freedom and self-determination, but there were also more personal motivations, e.g. the perception of suffering, oppression, injustice. These feelings clearly reflected the dominant political LTTE narrative23, but were often also based on personal experiences or on those of neighbours and friends (Alison 2003a, 45; Alison 2003b, 39-44). Many girls also joined the militant movements following the examples of their brothers or relatives. Hellman-Rajayanagam has translated some Tamil poetry where a young girl mourns her brother who died in the struggle and decides to follow his example: Several of Alison’s respondents also mentioned the disruption of their education. The LTTE promoted education. A female farmer listed the following educational services set up by the LTTE in her area: ‘They created Sivakumar Library to provide educational services. They offered computer and technical education through the Tamil Rehabilitation Club. They arranged for adult education through the Kantharoopan Knowledge Services’.25 Alison’s respondents also mentioned protection against (the fear of) sexual violence, which reportedly became wide-spread under the IPKF. Most of Alison’s interviewees did not join the movement for reasons of emancipation or personal advantage, but did indicate their increased awareness about women’s conditions and rights since their participation in the LTTE. Several of them said they had been liberated from all types of restrictions that traditional Tamil society had put on them earlier and felt more independent now. They drove bicycles, cars, and tractors, went out alone at night, and learned to swim and fight. At home, girls were told not to go on boats as ‘they will make the seas rough’; interestingly, a large percentage of the Sea Tigers were women (Alison 2003a, 59). Adele Balasingham, who was married to Anton Balasingham, the main ideologue and negotiator of the LTTE and a life-long companion of LTTE-leader Prabakharan, endows the women fighters with a lot of revolutionary agency: Regardless of these statements coming from a prominent member of the LTTE, it can be reasonably assumed that, in the case of LTTE women, ‘the restrictions on creative expression for women and the evils of the dowry system are some of the social factors that led to their initial recruitment’ (Thiranagama, quoted in de Silva 1994). Thiranagama (2011, 196) further clarifies that ‘… young people’s desire for radical change was most pressingly related to household and family expectations and obligations for marriage and dowry. Young unmarried men and women saw joining the militant movements as freeing themselves from these obligations, especially of dowry’. However, the LTTE also expected every family to contribute a member to the ‘liberation struggle’. This left families with little choice than to obey, as these demands were often backed with coercion (Terpstra & Frerks 2017). The movement stood also accused of recruiting child soldiers, although they argued themselves that most of these children did join out of their own volition or because they had nowhere else to go. One female respondent said that the LTTE regularly visited the schools and also had provided training classes for self-defence.27 The LTTE also used performances and videos for recruitment. A female teacher told us: It is not known exactly how many girls or women were recruited in this way. Alison refers to only one case of forced recruitment in her sample. There is, however, evidence of both significant voluntary and forced recruitment. The latter happened especially at moments the LTTE was short of ‘fighting hands’, due to refuge, displacement, and other losses. Swamy (2010, xliii–xlvii) describes how, especially after Karuna’s 2004 defection with about 5,000 former LTTE fighters in the East, the LTTE started a desperate and shameful campaign to forcefully recruit or (re-recruit) fighters, many of which were under age, including girls. Between 2002 and the end of 2007 alone the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission and international NGOs received over 6,000 reports of child recruitment by the LTTE and the Karuna faction (Frerks & Stöpler 2010, 207). 5.2 Fighting with ‘the boys’ LTTE women initially performed paramilitary and support roles, but they fully took part in armed combat after 1985. In 1989 they established a fully independent, special Women’s Military Unit of the Liberation Tigers under female command. The LTTE reportedly did not discriminate on the basis of sex when it came to training and combat operations, and operated under the slogan ‘equity for the nation and equality at home’ (Manoharan 2003). A 1993 report written by Adele Balasingham gives an insight in how women became fighters in the LTTE from 1984 onwards, how they were trained, and in which operations they participated. The training focused on mental and physical fitness, mastery of weaponry, and ‘the creation of highly politicized, determined cadres prepared for supreme sacrifice to achieve their political objective—a liberated homeland’ (Ann 1993, 19). Balasingham describes in fairly large detail several battles and raids during the Eelam Wars I and II, and how women took part in combat against both the Sri Lankan and Indian ‘occupation armies’. The first female martyr was Malathi, who died on the 10 October 1987 in the war against the Indian Peace Keeping Force. According to Balasingham, by the end of 1992, 381 women fighters had died, several of them taking the cyanide capsule rather than falling into the hands of the enemy. Apart from their role in combat, women were also member of the highest decision-making body of the LTTE, although still a minority (Alison 2003b, 47). Until the defeat of the LTTE in May 2009, women were reportedly inducted in all units of the organization—fighting, political, administrative, communication, intelligence, and social services. During the cease-fire agreement, when LTTE delegations visited European capitals, several women were included in those delegations.29 5.3 Heroism and martyrdom The LTTE fighters were held in high esteem among large parts of the Tamil population. They were admired for their bravery and their preparedness to fight and die for the cause of Tamil liberation. Hellmann-Rajanayagam states in this connection that ‘[the LTTE] are seen as the legitimate, traditional protectors of the people, because their rhetoric runs along lines which are [ … ] deeply entrenched and thus strike a related chord among the population: we protect you, your nation, your honour, your women’ (Hellmann-Rajanayagam 1994, 136–7). Cadres who lost their lives in the struggle were celebrated and worshipped as heroes and a veritable cult of martyrdom emerged, which was also vigorously promoted by the LTTE to garner legitimacy in the eyes of the population.30 The LTTE set up the Office of the Great Heroes of the LTTE, which was ‘devoted toward researching, evolving and producing hero symbolism and new sacrificial and religious terminology’ and also was in charge of maintaining the cemeteries (Thiranagama 2011, 213; Roberts 2014, 56). Maaveerar naal (Great Heroes’ Day) was declared 27 November to commemorate Lt. Shankar, the first LTTE cadre who died in combat; annually on this day the fallen cadres were commemorated with extensive rituals and ceremonies, including a speech by LTTE leader Prabhakaran broadcast on the LTTE radio. Schalk says that Shankar was ‘made a collective focal point to re-experience the mourning experience with its predictable outcome. The outcome is clear, to create a preparedness to kill and to get killed in the act of killing’ (Schalk 1997). The element of total self-sacrifice and total dedication to the cause of Eelam was also symbolized by the cyanic capsule—kuppi in Tamil—that the LTTE cadres were to swallow if they fell in enemy hands (Roberts 2014, 52–3). LTTE fighter Sita also evinced the ideals of altruistic martyrdom in an interview with Margaret Trawick (1999, 152–6), as did the young girl in the earlier poem by Cevvanam. On Heroes’ Day small shrines were erected in Tamil villages where flowers were offered and the fallen heroes worshipped. A businessman from Kilinochchi divulged that ‘People paid homage to their heroes. We must think that every militant of today is tomorrow’s hero. We should keep this in mind and celebrate Heroes’ Day till we die, praising their achievements and sacrifices they made for us’.31 Cultural performances were also part of this day, often drawing on martial poems and songs in Tamil. A driver from Mullaitivu recounted that the ‘… LTTE remembered the heroes on the Heroes’ Day by putting up stages, displaying photographs and conducting many events with songs and poems’, and concluded by saying ‘Every hero is a member of our family’.32 The re-enactment of existing songs or the composition of new ones has led to the popular pulippatukal or ‘Tiger songs’ that, according to Schalk (1997), were distributed by the LTTE on cassettes and CDs all over the world. Roberts signals that ‘Martyrdom was a critical factor in drawing popular support among the Sri Lankan Tamil people’ (Roberts 2009, 222). One respondent from Mullaitivu declared that Roberts states that apart from Heroes Day, at least nine other commemorations were organized every year (Roberts 2010, 245). For example, every year the first female LTTE martyr Malathi was publicly commemorated on the anniversary of her death (Manchanda 2001, 22). It has to be noted that from the moment that the LTTE controlled territory they also established cemeteries—tuyilam illam—for the fallen heroes with tombstones that have been turned in holy, sacred places. Roberts explains that the fallen heroes represent seeds that are able to bring new life, to regenerate, and to recall ancient Hindu rituals and cosmology (Roberts 2014, 58). He continues and says that ‘the creation of these sacred sites in this manner, clearly, has great political advantages in providing centres of inspiration and legitimation’ and that ‘there can be an instrumental, manipulative dimension to these activities in the minds of those calling the shots. The Tiger dead are a potent symbol of mobilization and legitimization’ (Roberts 2014, 94, 96). 5.4 Victim versus agent? Feminist empowerment or nationalist subjugation? Is the armed participation of women in the LTTE an act of agency and a sign of empowerment, or does it reflect a subjugation to a reprehensible masculine nationalist project and order? This issue has raised intense debate among feminists and academics both in Sri Lanka and internationally. Whereas those writing from a LTTE perspective such as Schalk and Balasingham, and also some outsiders like Alison, generally celebrate female LTTE cadres in terms of agency, emancipation, and liberation, others take a more nuanced or outright critical stance. Conceptually, the literature on women fighters situates itself around a debate on victimization versus empowerment. Women taking up arms are felt to defy tradition and consequently this image of ‘woman warriors’ has been targeted by conservative critics as ‘unnatural’ and ‘undermining the values of (patriarchal) family and society’ (D’Amico 1998, 120). But women fighters have also perplexed feminists. Radical feminists have embraced the notion as a form of women’s power defending and liberating women, while liberal feminists basically stress women’s equality in military settings, and its potential to reform military institutions. Critical feminists, however, reject women’s involvement in militaries, as they become subject to a hierarchical process of militarization and can only fail to feminize the institution (D’Amico 1998, 120). Others take a less binary view. In many cases the notion of ‘empowerment’ during conflict is ambivalent, as it comes with high mental and physical costs, losses, and suffering. Rajasingham-Senanayake suggests that agency comes at moments when women seem most victimized, while she also argues that female combatants in nationalist struggles are often subsumed in conservative nationalist reconstructions of women and tend to subordinate their gender identities to the nationalist cause (Rajasingham-Senanayake 2001, 111, 127–8). Others have challenged this view stating that commitment to one’s nation or ethnic group can be as important or more important than one’s needs as a woman (Alison 2003a, 65–6). Samarasinghe (1996, 204–5) makes the distinction between situational and strategic positions of women during war. The first are extensions of the traditional reproductive role of women in the private domain of the domestic sphere, while the second is placed in the public sphere in relation to the war itself, with newly assumed identities of soldier/revolutionary, martyred mother, and peacemaker. It is often argued that the experiences and transformations wrought by war do irreversibly alter deeply gendered conventional, and often oppressive, societal traditions and cultural practices. Adele Balasingham describes how many bystanders were shocked when the rifle-carrying women guerrillas of the LTTE marched into Jaffna wearing camouflage uniforms after the withdrawal of the Indian Peace Keeping Force: Schalk (1992, 110–12) adds to this that ‘LTTE women reflect on their situation and the programs of the LTTE Women’s front undermine and counteract the factual hierarchical structure and male dominance of Jaffna society’. Coomaraswamy (1996) admits that there have been important changes in the daily lives and practices of Tamil women due to the fighting, the displacement, and the LTTE’s strategy, but she doubts whether these will be permanent after the ‘inter-regnum’ of war. Moreover, she argues that LTTE women were subject to a larger nationalist and military project by men without having any decision-making power and, hence, were in effect disempowered. She also critiques the ‘LTTE innovation’ of the ‘armed virgin’ as an androgynous construct, which has no base in Tamil culture and eradicates earlier existing forms of femininity and diversity. Also, Sumathy severely criticizes the notion of martial feminism or martial chastity attributed to the LTTE and resonated by writers like Schalk (Sumathy 2004, 129–36). De Silva (1994, 27–31) argues that the LTTE’s male constructed, nationalist project holds a bleak future not only for the feminist agenda, but also towards women’s liberation. Perera-Rajasingham, Kois, and de Alwis (2007) also raise the question: They argue that: Senanayake and Alison stress in this context that the opposing notions of agent/victim, liberated/subjugated, and emancipated/oppressed are unsophisticated binaries, with the reality being ambivalent and multifaceted. The debate on the nature of female LTTE combatants is illustrative of the different political and theoretical stances of the writers in question and will largely depend on the paradigms chosen to highlight the issue. 6. Conclusion This chapter has discussed the active involvement of LTTE women in combat, and that they appeared to join the movement for a variety of reasons resembling those found in the broader literature, such as ideological and political motivations, poverty, and unemployment. There were also reasons related to the particular conditions in Sri Lanka, such as grievances against the way the Tamil minority was treated by the Sri Lankan government and protection against sexual and gender-based violence by Sinhalese soldiers and the IPKF. The resistance against arranged marriages, dowry, and repressive family life were factors specific to traditional Tamil society. It showed that since the mid-1980s female LTTE combatants became fully fledged members of the LTTE forces, including the Sea Tigers and the Black Tigers who were trained as committed suicide commandos. They underwent the same training as their male counterparts and fought side by side with male combatants. The same legitimations and sacrificial martyrdom that were cultivated by the movement were applied to them and seemed to have motivated them as well. It also showed that the LTTE fighters, including the female cadres, were generally held in high esteem among the Tamil population in the North and East. The debate on women fighters is surrounded by different and contradictory societal perspectives and theoretical positions, and also has divided feminists. This refers especially to the supposed victimizing, liberating, or empowering effects of female participation in armed struggle. It can be safely concluded that the participation of women fighters has negative and victimizing aspects as well as empowering dimensions. Some authors stress the emancipating effects, while others only see subjugation to a nationalist, male-centred project. There is a huge debate on which dimension dominates or what combination prevails in practice. Some authors reject a binary position and argue that the situation is in fact ambivalent by nature. The Sri Lankan case seems indeed to embody this ambivalence, but I suggest that any final conclusion will largely depend on the paradigms chosen to highlight the issue. Notes 1 Earlier work by Frerks on gender and conflict includes Bouta & Frerks (2002), Frerks & Bouta (2003), Bouta, Frerks, & Bannon (2005), Bouta, Frerks, and Hughes (2005), Frerks (2014), Frerks, Ypeij, and Soriria König (2014), and Bateson, Dirkx, Frerks, Middelkoop, and Tukker (2016). 2 See Terpstra and Frerks (2015; 2017). 3 See a.o. Elshtain (1995), DeGroot (2001), and Moser and Clark (2001). 4 See a.o. McKay and Mazurana (2004), and Karame (1999). 5 Figures of casualties vary widely; higher estimates mention figures up to 120,000. This is partly due to the violent end of the war in which many people disappeared or were killed. This episode is of great political controversy and is currently subject to an international investigation by the UN Human Rights Council into alleged war crimes and violations of human rights. 6 See a.o. Frerks and Klem (2005), McGilvray (2008), Swamy (2010), Peiris (2009), de Silva (2012), Solnes (2010), Spencer et al. (2015), Wickramasinghe (2006), and Weiss (2012). 7 Sri Lanka was officially called Ceylon till 1972, but for simplicity’s sake I refer to the country as Sri Lanka when I discuss pre-1972 events or developments. 8 Karayar is the fishermen’s caste and Vellala the farmers’ caste. 9 The LTTE was not unique in this regard. Other militant Tamil groups had women’s committees and women fighters. See Thiranagama for details on the EPRLF (2011, 193). 10 Interview 2.1, Mankulam, 16 February 2015. 11 Interview 2.1, Mankulam, 16 February 2015. 12 Interview 2.2, Kilinochchi, 17 February 2015. 13 Interview 2.4, Puthukudiyiruppu, 18 February 2015. 14 Interview 1.2, Vaharai North, 17 February 2015. 15 Interview 1.3, Vaharai, 17 February 2015. 16 Interview 2.2, Kilinochchi, 17 February 2015. 17 Interview 12-NB4, Kilinochchi, 19 March 2016. 18 Interview A-A1, Mankulam, 18 March 2016. 19 Interview 10-NB2, Mankulam, 18 March 2016. 20 Interview 3.4, Puthukudiyiruppu, 18 February 2015. 21 Interview A-A1, Mankulam, 18 March 2016. 22 Interview B-B1, Mankulam, 18 March 2016. 23 See Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam 2005. 24 Cevvanam, A Few Tears for the Darling Resting in the Sepulchre; translated by and included in: Hellman-Rajanayagam (2004, 121). 25 Interview A-A2, Mankulam, 18 March 2016. 26 In 1993 Adele Balasingham still wrote under her maiden name Ann. 27 Interview 2.2, Kilinochchi, 17 February 2015. 28 Interview 1 NA1, Mankulam, 18 March 2016. 29 Own observations by the author when LTTE delegations visited the Netherlands during the CFA on two occasions and he was asked by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Norwegian embassy (that had arranged for the trip) to chair the meetings with the LTTE delegation. 30 See Terpstra and Frerks (2017). 31 Interview 11-NB3, Kilinochchi, 18 March 2016. 32 Interview 13 NB5, Mullaitivu, 19 March 2016. 33 A pooja is the act of showing reverence to a god, a spirit, or another aspect of the divine through invocations, prayers, songs, and rituals, including the offering of flowers, fruits, food, etc. It can also be performed in honour of a special guest or to commemorate persons who have died. 34 Interview 22 NC06, Mullaitivu, 19 March 2016

-

- tamil tigress

- tamil tiger women

- (and 3 more)

-

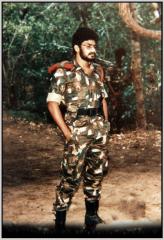

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

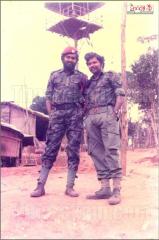

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

4cd18e7f756cfa88d121bbfa6417da286b6d42f1UlMa271kMF53jTvqFHZC.video_thumb_5753_317.2.jpeg

நன்னிச் சோழன் posted a gallery image in விம்பகம்

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

138796880_424740791909644_8181421906639129890_n.jpg

நன்னிச் சோழன் posted a gallery image in விம்பகம்

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

150144156_3840467326038260_2195430811353993240_n.jpg

நன்னிச் சோழன் posted a gallery image in விம்பகம்

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)

-

From the album: தமிழீழ விடுதலைப் புலிகளின் படிமங்கள் | Tamil Tigers images

-

- ltte images

- tamil tiger images

- (and 4 more)